Meet diatonic scales in music, through an analogue clock

The A minor scale is related to C major, in that they share the same, empty, key signature. These scales are two different sevenths of white keys on the piano. Because the notes are repeated in octaves, there could be five other different sets of white keys, that is with the same, blank, signature, defining different tonalities. I understood that, in the most, the two mentioned above were imposed, but I always wondered about the other, blank-signed, scales.

Having been delighted by the ease by which the “music clock” offered me, in regard to the circle of fifths, I decided to read up on the fundamentals of music theory, in case the clock would help me to understand theory more easily. I quickly stumbled upon the five “lost” tonalities of the white keys of the piano.

When, in addition to the major and minor scales, we take into account the other five scales of the same signature, we have seven diatonic scales, where the usual major and minor scales are just two diatonics out of seven.

Diatonics’ modal brightness

I’m not a musician and I can’t distinguish the diatonics acoustically, however I read in text their classification, depending on how bright or dark they sound. My aim is, with the help of the music clock, to reproduce the classification of diatonics and achieve a comparison between two of them easily.

Let’s see the music clock

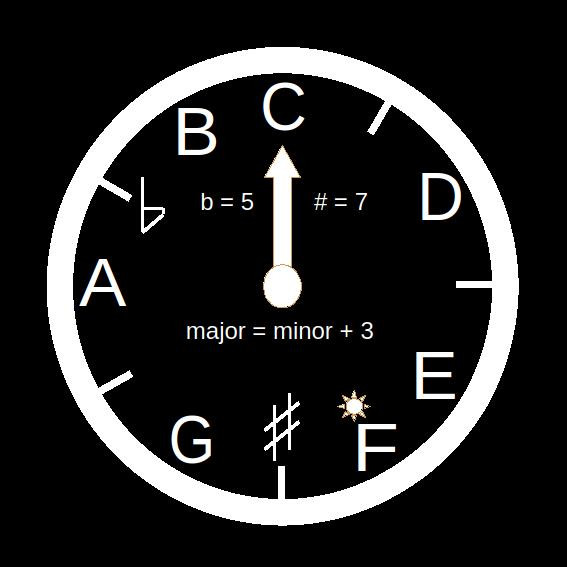

Our music clock

Since only the white keys are used, the clockwise jump from natural tone to natural tone corresponds to an upward scale. Thus, small lines are easily recognized as an intervals of a whole tone. Starting from any natural tone, a clockwise, twelve hour, complete turn corresponds to that tone’s diatonic.

A fictional story is an indispensable mnemonic tool. We consider the jump from tone to tone as an ascending scale. A jump by a whole tone corresponds to a step. A half-tone jump corresponds to a landing that offers rest. In each diatonic, a melody starts from its basic tone and follows an ascending progression back to it, e.g. (C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C). The mode of the diatonic, I believe, is expressed by the mood of the melody using it. I distinguish two cases:

- As long as the melody is eager to get high quickly, it tries to use steps (whole tones) from its very first movements. Then it happens to reach the tonic rested and cheerful. Therefore, her mood is brighter, hence the mode of the diatonic is brighter.

- As long as the melody is reluctant to go up the scale, it tries to use landings (semitones) from its very first movements. Then it happens to arrive at the tonic tired and unmotivated. Therefore, her mood is darker, hence the mode of the diatonic is darker.

Comparison and classification of diatonics

We will denote movement by a whole tone by the letter W (Whole) and movement by a half tone by the letter H (Half).

In our imaginary story:

diatonics that start with H are the most reluctant to start aggressively, even by one step W. Thus, they are the darkest diatonics.

Next, the diatonics which, being less reluctant, start with one W step, i.e. W-H, and thus are less dark than the first ones.

Both of the previous two categories of diatonics, in the texts, are considered to be minoritic (The first third interval, from the start, is minor).

Diatonics that start with two steps W, i.e. W-W-H, are brighter than those that start with one step W, and even brighter are those that start with three whole steps W, i.e. W-W-W-H. In texts, the last two categories of diatonics are considered majoristic (The first third interval, from the start, is major).

With respect to brightness, we have already the arrangement

H < W-H < W-W-H < W-W-W-H.

Let’s define a strict order to the set of seven diatonic scales.

- H: Looking at the clock, we see that there are two tonalities that begin with a semitone. At 4 o’clock, the E, and at 11 o’clock, the B. But B reaches its key note more tired, after 3 W steps (before which it rested on the E-F flat), than E, which reaches its key note after 2 W steps. Thus, B is darker than E (B < E).

- W-H: We find that there are two tonalities beginning with W-H. At 9 o’clock, the A, and at 2 o’clock, the D. But A reaches its key note more tired, after 2 W steps, than D, which reaches its key note after 1 W step. Thus, A is darker than D (A < D).

- W-W-H: We find that there are two tonalities that begin with W-W-H. At 7 o’clock, the G, and at 12 o’clock, the C. But C reaches its key note more rested, after an H step, than G, which reaches its key note, somewhat tired, after 1 W step. Thus, C is brighter than G (C < G).

- W-W-W-H: We find that there is only one tonality so eager to climb the ladder that it begins with W-W-W-H. At 5 o’clock, the F, which is the brightest of all. (This is exactly what the sun symbol above the F note on the clock reminds us of.)

With the help of the short mnemonic fictional story and the visualization of the steps on the clock, the strict order of the seven diatonic scales was created, same as we read in the texts. Let us sort them from the lightest to the darkest. The identification is based on the unique step sequence of each one. For example, from the sequence H-W-W-W-H-W-W it is clear that it is the 4th hour or the E tone or the Phrygian diatonic.

Classification of diatonic scales

| diatonic | Lydian | Ionian | Myxolidian | Dorian | Aeolian | Phrygian | Locrian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hour | 5 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 11 |

| tone | F | C | G | D | A | E | B |

| mode | brighter | darker |

Conclusions

The immediately darker diatonic scale occurs 7 hours (#=7) later than any current one.

Conversely, the immediately brighter diatonic scale occurs 7 hours earlier (-7) than any current one, equivalently, occurs 5 hours (b=5) later than any current one.

Continuous clockwise or counterclockwise movement, 7 hours at a time, does not bring out additional modes.

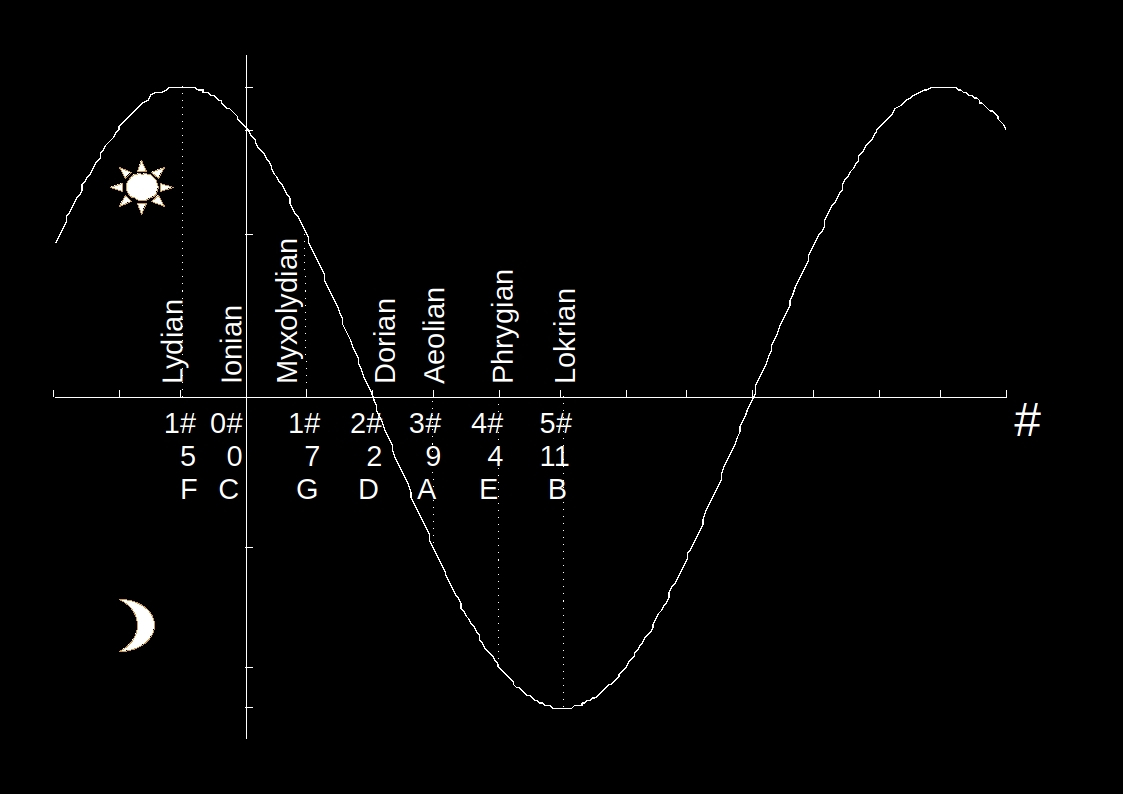

As we have seen with the circle of fifths, the continuous turning of the clock hand, 7 hours at a time, will eventually arrive at the time from which it began. This means that, since, in general, moving (#=7) hours decreases brightness and, at the same time, ends up at the same brightness, there is a brightness minimum. Similarly, since, in general, moving (b=5) hours increases the brightness and, at the same time, results in the same brightness, there is a brightness maximum. By an arbitrary quantification of the brightness of diatonic scales, the above is shown in the following diagram.

Diagrammatic representation of the modes of diatonic scales

It becomes clear that after the darkest Locrian or B or 11th-hour diatonic, the movement by # (#=7) gives the 6th-hour diatonic or F#, which does not exist, as not being related to the blank signature (at least its fundamental tone is in sharp), and, even if it did exist, it would be expected to have the mode of the Phrygian diatonic. Similarly, after the brightest Lydian or F or 5th-hour diatonic, moving by b (b=5) gives the 10th-hour diatonic or Bb, which does not exist, as not being related to the blank signature (at least its fundamental tone is in flat), and, even if it did exist, it would be expected to have the mode of the Ionian diatonic.

Finding chord alterations

Occasionally we need to alter the tones of a chord so that it is considered to be based on some degree of a church mode. Since all church modes correspond to some degree of C major, with unaltered tones, it is easy with the help of the music clock syllogism to find the necessary alterations. The syllogism was developed in the above-mentioned article so let’s look directly at an example.

It is irrelevant, for the purpose of finding the alterations, to what degree of what scale we are in, but let us assume that we are in the D major (D=2 o’clock ~ 14, where 14/7=2 so the key has #F and #C) as well as in the VI of this scale, i.e. in B with B-D-#F.

Suppose we want the chord in B to correspond to the 4th degree of the Myxolydian type. The Myxolydian mode, with reference to the C major, begins at G (7 o’clock). The 4th degree from G exists at C (12 o’clock) 12-7=5 hours later. So 5 hours earlier than the 4th degree of B is the initial tone of the Myxolydian mode, in this case B(11) - 5 = 6 o’clock = #F. So we want the alterations that identify the myxolide type starting at #F.

Since the myxolydian mode, with regard to the C major, starts at G (7 o’clock) and the corresponding major scale occurs 5 hours later, then 5 hours later than the original #F, i.e. at 6+5=11th hour (B), the corresponding major (B major) occurs. So the alterations are 11+2*12=35, 35/7=5 sharps, #F, #C, #G, #D and #A.

Equivalently and more briefly, we can say that, with respect to the major scale (C = 0 o’clock), the 4th degree of the myxolidian (G-A-B-C = C = 0 o’clock) occurs at the same hour of the corresponding major scale. So with respect to the B chord, that we wish to identify as the 4th degree of the myxolidian, the alterations correspond to the major scale of the same hour, i.e. the B major scale.

According to the above, instead of B-D-#F, which we would use in tonality, we alter to B-#D-#F.

Another example:

We want the seventh chord of the 5th degree Dorian mode (with reference to the C major beginning with D). The 5th from D is A (9 o’clock) so the corresponding major (C) occurs 3 hours later. Suppose we want the initial pitch of the chord to be F (5th hour). We need the alterations corresponding to the major 3 hours later, at the 5+3= 8th hour major. 8+12=20, 20/5=4, so 4 flats (bB, bE, bA, bD). Therefore, we use the F-bA-C-bE seventh chord.

Reasoning example

We know that when changing scales, we usually choose the “closest” scales whose keys differ by only one alteration. For simplicity, let us assume that we are in C major. The transition to another major is usually made either on the 4th degree (IV=F major with bΒ) or on the 5th degree (V=G with #F). We can use the same logic to alter some chord-to-chord progression.

Suppose we wish to alter the first chord in the V-vi progression (for our example of C major, progression from the G to A). We can assume that the 2nd chord in A is defined over some church mode and define the chord in G in relation to that mode. The closest types will have a basic major scale of either G(V) or F(IV).

In the first case, the chord on A will belong to the Dorian type (D) (which has the basic major scale in G). The notes of this type used will be G(C)-A(D)-B(E)-C(F)-D(G). (The initial tone of the Dorian type D on the desired tone of A has been placed in parentheses to help, through the intervals of the C major, in the calculation of the alterations.) We see that on the G-B-D chord there is no alteration.

In the second case, the chord on A will belong to the Phrygian type (E) (which has the basic scale major in F). The notes used in this formula will be G(D)-A(E)-bB(F)-C(G)-D(A). We see that on the G chord G (G-bB-D) the B is altered to bB. That is, instead of the transition V-vi, with chord G major (V), v-vi, with chord G minor (v) is used.

Note

I think that, in the musical clock, the symbolism of F as the brightest diatonic is sufficient. E.g. the brightness can only be lowered and moving by b results in an accidental tone, thus in a dead end. Only moving by # offers a way out. So, even if we don’t remember, we can conclude that moving # darkens the mood, while b brightens it.

I don’t know about music but, from a mathematical point of view, I found the relationship between musical clock and diatonic scales amusing.

(Important reference: A few months after writing this, I came across the amazing, in every respect, website Integrated Music Theory of which I could not fail to mention it).